Improving safety, managing pain with trust and rapport

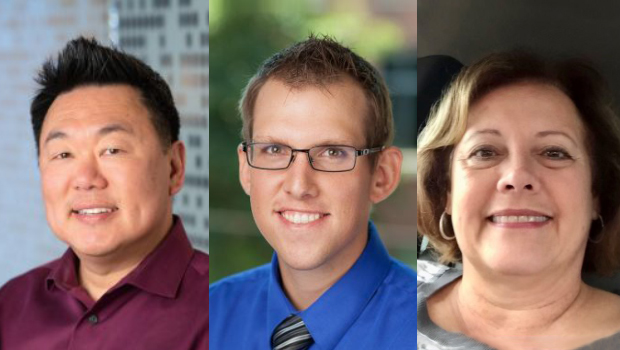

L-R: Ed Wakatake, Ryan Gonce, and Cherie Sierra

Puyallup team excels at patient-centered care and improving opioid safety for people with persistent pain

By Paula Lozano, MD, MPH, associate medical director for research and translation at Kaiser Permanente Washington, senior investigator at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, and director of the institute’s Center for Accelerating Care Transformation

Across Kaiser Permanente Washington, care teams are finding ways to support people with persistent pain while ensuring the safety of opioids prescribed to manage pain. In most cases, experts do not recommend taking opioids for ongoing pain because the dangers of long-term use typically outweigh the benefits.

Back in 2019, the Center for Accelerating Care Transformation (ACT Center) partnered with the Puyallup Medical Center to design the Integrated Pain Management (IPM) Program, a whole-person approach to caring for people who take opioids for persistent pain. Puyallup Medical Center’s Ed Wakatake, MD, Ryan Gonce, PA-C, and Cherie Sierra, RN, had a major influence on the design of the IPM program, including launching an Opioid Safety Committee (OSC). Since piloting the OSC at Puyallup, the ACT Center has been helping to spread this innovation to other medical centers in the region.

In 2021, Kaiser Permanente Washington’s Quality and Safety department offered a Maintenance of Certification (MOC) course focused on reducing high-dose opioid prescribing. Participating providers across the region achieved an average 23% reduction in the number of members on high-dose opioids. The results from PA Gonce and Dr. Wakatake were particularly impressive: a whopping 73% decrease in high-dose prescriptions among their patient panels.

When I talked with this standout team from Puyallup, they emphasized that improving opioid safety starts with building trust and rapport and knowing the values and goals of the people they care for. Here’s more from my conversation with the Puyallup Medical Center’s Ed Wakatake, Ryan Gonce, and Cherie Sierra.

What did you do that led to these stellar results?

EW: I aim to make a plan with patients that takes their whole person into account. I ask how they feel physically, what their life is like, what their goals are, and what their concerns might be. Many people feel stuck on medications as the only way of managing pain and don't want to cut back. In fact, long-term opioid use can actually make pain worse by making a person more sensitive to pain. Also, opioid side effects are common and can be serious. While cutting back can be challenging, there are real benefits.

RG: Trust and rapport are essential. I focus on communicating well so that the patient and I understand one another. I talk to patients about the risk of opioids and what their future may look like when taking a decreased dose. When a patient speaks with any member of our team, they hear the same messages about their care plan and safety.

EW: Reducing the number of high-risk prescriptions was definitely a team effort. One provider couldn’t do it alone. The whole care team was engaged including Cherie, Ryan, and other care team members, like social workers and pharmacists.

CS: Every month there is a meeting of our medical center’s Opioid Safety Committee (or OSC), a group of staff who work to reduce risky opioid prescriptions. The OSC supports providers to improve care for their patients on opioids. We’re all working toward the same goals.

How does the OSC support this work?

RG: The OSC closely reviews the chart of each patient on high dose opioids, then meets with the provider to talk through the case, share recommendations and best practices, and come to consensus on a care plan that centers a patient’s concerns and goals. We also make providers aware of great resources available for them and their patients. The OSC has been especially helpful to providers who have struggled to find the best course of action for some patients. It really helps that, as colleagues, we know and trust each other.

When you are talking with patients about ongoing pain, what do you say?

EW: I don't ask about pain or meds right away. Instead, I ask about a patient’s life. I say, “What do you want out of life? Is it time with grandchildren? Travel? I want to help you achieve your goal.” Spending time getting to know their stories and aspirations helps me understand what might be best for their care. I can’t do this all in one visit, so I make a point of seeing patients often to build the relationship.

I’ve also found that, before tapering starts, it’s helpful to share tools for coping with pain and to talk about options for complementary or alternative treatment and therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy.

RG: Before we jump into a medical discussion, I listen to understand my patient’s woes and fears so I can connect with how they might be feeling. We need to address safety standards, but not before empathizing — it's a package deal.

When people can see that I understand where they’re coming from, we can talk about how their life will improve without opioid medicines. That’s when I talk about the physiology of opioids and how their regimen might be exacerbating side effects. Many people rely on these medications for their quality of life — some can’t even remember what life was like before opioids. Explaining some of the science of opioid medicines can help build understanding of how life can really improve with a good plan in place.

CS: I talk with patients about what to expect as we work together, like regular visits to adjust their care plan and urine drug screens to ensure their safety. Knowing what to expect helps build trust.

What do you do when patients experience challenges as they try to taper opioids?

CS: Sometimes patients do need extra support when they are tapering their opioids medications. I identify those patients and provide care management, touching base periodically to support them and help them stick to their plan for managing pain and reducing opioid medicines. This sometimes means adjusting the plan to meet the patient where they are at. I let them know that we are here for them through the ups and downs.

Featured resources

Written by patient partners this bilingual toolkit offers support and resources for people with persistent pain.

Related news